HISTORY

So, in brief summary we have, starting in 1429 and in successive waves thereafter an imposed a ban on all weapons even rusty swords, by the peasant class. At the same time we have increasing communication between Okinawa and the Chinese mainland which had a strong martial/weapons tradition.

The two theories most strongly suggested for the development of kobudo are:

1. They, very much karate, developed largely from Chinese traditions, transported to Okinawa from as early as 700 CE.

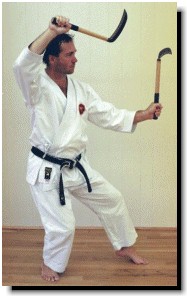

2. They were developed independently by the people of Okinawa, in response to the ban on real weapons, that is the weapons of the samarai and higher classes, by the Japanese. They evolved from farming implements. The bo was the stick slung over the shoulders and used to carry water. The kama was the sickle used to harvest the rice. The sai was the pitchfork. The nunchuks were the flails that separated the grain from the chaff. The tonfa was the handle of the mill stone used to make flour. And the eku or Iyeku was, of course, the oar.

In support of the first theory we have the records indicating that the

organization of kobudo  only

really began in the 1600's, as wealthy Okinawan went to China and learned

the use of the weapons for pleasure. There are no records, certainly of

the Okinawans using these weapons on a military (as against the katana

of the overlords) or even a consistent scale.

only

really began in the 1600's, as wealthy Okinawan went to China and learned

the use of the weapons for pleasure. There are no records, certainly of

the Okinawans using these weapons on a military (as against the katana

of the overlords) or even a consistent scale.

The bo appears to be a fairly universal weapon. It is after all, a long stick. The tonfa is a handle - for a mill stone, a handle for the village well. The oar as weapon appears unique to Okinawa and while sais certainly resemble pitchforks, they are generally attributed as a weapon invented by the Okinawan police-it has been suggested that the idea came from the nails used to pin the large wooden blocks together in large buildings. The sai also appears in other oriental weapon traditions but its use against the katana seems dubious. The construction techniques in non-modern times would place the crudely constructed sai at tremendous disadvantage against the long tradition of craftsmanship seen in sword making and the spacing of the short arms much more appropriate against a bo than a sword.

While these are by far the most commonly seen weapons, there are others.

Left out of this more romantic origin tails are the rest of the 'traditional' weapons of kobudo, the nunti-bo (a bo with a nunti-sai mounted at the tip), tinbe/rochin (short spear/shield), kuwa (Okinawan hoe), suruchin (bolo), abumi (a wooden saddle stirrup), yari (spear), tekko (the Okinawan brass knuckles), the shu-chu or tettchu (small hand weapon), and of course, the katana and naginata which are obviously not native.

On the other hand it's interesting to note that many of the weapons found in traditional Chinese arts seem to have found no champion and so died out of the Okinawan tradition.

But the tradition that seems to have driven the development of these weapons is that of famous/legendary practitioners whose legacies are soundly stamped on the kata practiced today.

In the Shorin Ryu tradition Chatan Yara (born in the village of Chatan, Okinawa in 1670) contributed much. He reportedly studied in China for 20 years and left kata such as Chatan Yara No Sai.

Most modern karate styles can be traced back to the famous Satunuku Sakugawa

(1733- 1857)

(this rings a bell!), called 'Tode' Sakugawa. He first studied under Takabara

Peichin (also known as Chinen Pechin) of Shuri and later went to China

to train under Master Kusanku. His return to Okinawa in 1762 is credited

in the shorin ryu tradition as being the introduction of karate to Okinawa.

Sakugawa became a famous samurai and had many famous students - Matsumura

Chikatosinumjo Sokon, Makabe Satunuku, Ukuda Satunuku, Matsumoto Chikuntonoshinunjo,

Kojo of Kumemura, Bushi Sakumoto, and Usume of Andays.

1857)

(this rings a bell!), called 'Tode' Sakugawa. He first studied under Takabara

Peichin (also known as Chinen Pechin) of Shuri and later went to China

to train under Master Kusanku. His return to Okinawa in 1762 is credited

in the shorin ryu tradition as being the introduction of karate to Okinawa.

Sakugawa became a famous samurai and had many famous students - Matsumura

Chikatosinumjo Sokon, Makabe Satunuku, Ukuda Satunuku, Matsumoto Chikuntonoshinunjo,

Kojo of Kumemura, Bushi Sakumoto, and Usume of Andays.

Another thread comes from the Shorin Ryu tradition of Tadashi Yamashita (who, in passing, has some really interesting videos available through Panther Productions).

The kata of kobudo provide insight and to some extent are the history of the art. Usually passed down from father to son, master to disciple, this mode of transition is a time honoured tradition. In almost every field we actually have very few written records that are over 100 years old. And, as with any knowledge that was seen as potentially dangerous to possess or that posed a threat to those in power, it was kept secret, camouflaged, or misrepresented to avoid persecution. This applies particularly to the Okinawan tradition where weaponry and martial arts training were specifically and repeatedly outlawed by the occupying forces of Japan.

It's been suggested that the traditional Okinawan dances or odori played

a part in the development of kobudo kata. They portrayed movements from their agricultural

life, including the use of simple tools. We can see this most in the forms

for the eku that feature rowing motions. Also perhaps because the eku

is not one of the most popular weapons, one has the suspicion that its

basic kata have had the least pressure to be updated.

development of kobudo kata. They portrayed movements from their agricultural

life, including the use of simple tools. We can see this most in the forms

for the eku that feature rowing motions. Also perhaps because the eku

is not one of the most popular weapons, one has the suspicion that its

basic kata have had the least pressure to be updated.

The influence from the dance is interesting because we also see it other martial arts traditions - some gung-fu and more recently capoeira. It also adds an interesting validity to the musical form concept. Enough written evidence exists to prove that formalized kobudo kata existed on the Ryukyuan chain of islands as early as the 1480s. The first account refers to Yaeyama, an island group south of Okinawa. The tribal chieftain, Oyekei Akahachi is credited with formulating bo and eku techniques and converting them into ritualized dance. These are the Akahachi No Bo forms.

This is a wonderful example of knowledge disguised for transmission.

The parallel that comes immediately to mind are the spirituals of the

Deep South in the early 1800s that included the instructions for contacting

the Underground Railway and the escape routes for the slaves, for example,

Follow the Drinking Gourd.

Later on and prior to 1868 the Yaeyama island group was used as a place of exile for deposed political leaders and other Okinawan gentry who posed a threat to the newly established administration on the main island of Okinawa. Peichin Tokumine (c. 1846-1928) was one such political exile.

While in exile he learned the Akahachi forms and became so proficient that martial arts masters visited him to learn his techniques, for example, 'Tode' Sakugawa. This lineage became responsible for many of the forms taught today.

Unfortunately many of the older kobudo kata faded out or never became known to later generations because some of the old masters never found suitable successors. Many practitioners used the training they received as a basis for developing their own versions of the techniques so that the forms were changed as they passed down the ladder of time.

The modern style that specifically sites Peichin Tokumine (also known as Yamane, or Chinen Pechin) as founder is Yamaneryu Bojutsu. The careful reader will note that above we have Sakugawa studying under Peichin, whereas here we are claiming that Chinen most favoured the traditions of Sakugawa and Shikiyanaka. Let's just say that such confusions are not unusual when reading the histories of the arts and leave it at that.

Chinen is credited with being a brilliant innovator whose most notable

legacy is the series of exercises Chinen Shikipanaka no kon. The hall

marks of this style are a swift circular motions, patterns of twisting

thrusts and pliable footwork resembling Sojutsu, the art of spearmanship,

and classically includes the five kata: Shuji, Sakugawa, Chinen Shikiyanaka,

Shirotaru, and Yonekawa.

In the resources section I've included some lists of kobudo kata from

some of the more prominent schools of kobudo. Kobudo styles are in general

associated with the empty hand style that they are associated with. Kobudo

as an independent entity only arises as extremely talented practitioners

came to the fore and added their inspiration to the art in general. In

your future readings on kobudo you will again encounter many of these

names.

So, in summary, we have a fairly unique style of weapon usage that originated,

under heavy Chinese influence on the small, geographically isolated Ryuku

Islands. Hear it developed and flourished, spreading eventually to Japan.

Kobudo in the sense used here does not properly include the weapons of

the ruling class, notably the katana whose use has been preserved under

independent traditions such as kendo and iaido. Something in the unique

character created a pattern of weapon usage very different from those

traditions in the adjacent China, Korea, and Japan.